The Carey Treatment

| The Carey Treatment | |

|---|---|

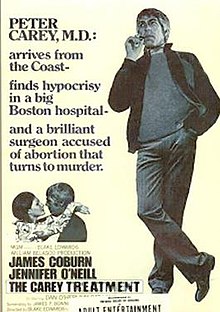

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Blake Edwards |

| Screenplay by | James P. Bonner (pseudonym for Harriet Frank Jr. Irving Ravetch) |

| Based on | A Case of Need 1968 novel by Jeffery Hudson (pseudonym for Michael Crichton) |

| Produced by | William Belasco |

| Starring | James Coburn Jennifer O'Neill Pat Hingle |

| Cinematography | Frank Stanley |

| Edited by | Ralph E. Winters |

| Music by | Roy Budd |

Production company | Geoffrey Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Carey Treatment is a 1972 American crime thriller film directed by Blake Edwards and starring James Coburn, Jennifer O'Neill, Dan O'Herlihy and Pat Hingle. The film was based on the 1968 novel A Case of Need credited to Jeffery Hudson, a pseudonym for Michael Crichton. Like Darling Lili and Wild Rovers before this, The Carey Treatment was heavily edited without help from Edwards by the studio into a running time of one hour and 41 minutes; these edits were later satirized in his 1981 black comedy S.O.B..[1][2]

Plot

[edit]Dr. Peter Carey is a pathologist who moves to Boston, where he starts working in a hospital. He soon meets Georgia Hightower, with whom he falls in love. Karen Randall, daughter of the hospital's Chief Doctor, becomes pregnant and is brought to the emergency ward after an illegal abortion. She dies there, and Dr. David Tao, a brilliant surgeon and friend of Carey, is arrested and accused of being responsible for the illegal abortion. Carey does not believe his friend to be guilty and starts investigating on his own, despite strong opposition by the police and the doctors around the hospital's chief.

Cast

[edit]- James Coburn as Dr. Peter Carey

- Jennifer O'Neill as Georgia Hightower

- Pat Hingle as Capt. Pearson

- Skye Aubrey (Susan Schuyler Aubrey) as Nurse Angela Holder

- Elizabeth Allen as Evelyn Randall

- John Fink as Chief Surgeon Andrew Murphy

- Dan O'Herlihy as J.D. Randall

- James Hong as David Tao

- Alex Dreier as Dr. Joshua Randall

- Melissa Torme-March as Karen Randall

- Jennifer Edwards as Lydia Barrett

- Michael Blodgett as Roger Hudson

- Regis Toomey as Sanderson the Pathologist

- Steve Carlson as Walding

- Rosemary Edelman as Janet Tao

- John Hillerman as Jenkins

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Film rights were bought in August 1968 by A&M Productions, the production company of Herb Alpert. They said filming would take place the following year in Boston.[3] In October Perry Leff signed Wendell Mayes to a two-picture contract to write and produce, the first of which was to be A Case of Need.[4][5][6]

Film rights were then picked up by MGM. In March 1971 it was announced Bill Belasco was producing and Harriet Frank Jr. and Irving Ravetch were working on a script.[7]

In June Blake Edwards signed to direct.[8] This was considered surprising because Edwards had clashed with MGM's chief executive, James Aubrey, during the making of The Wild Rovers. Edwards' wife Julie Andrews later wrote "for reasons I can only guess at, Blake took the bait. Perhaps there was some compulsion on his part to make things right, or perhaps he simply wanted to finally win out against the man who had caused him such pain."[9]

Aubrey promised Edwards he would finance The Green Man, a project of Edwards' to star Julie Andrews.

The cast included Aubrey's daughter Skye,

Shooting

[edit]Filming started in September 1971 under the title A Case of Need.[10] It was a difficult shoot with Edwards claiming Aubrey cut his schedule and refused to let Edwards rewrite the script. Edwards left the film after completing it.[11]

Edwards launched a breach of contract suit against MGM and president James T. Aubrey for their post production tampering of the film.[12] Edwards:

The whole experience was, in terms of filmmaking, extraordinarily destructive. The temper and tantrums from my producer, William Belasco, were such that he insulted me in front of the cast and crew and offered to bet me $1,000 that I'd never work in Hollywood again if I didn't do everything his and Aubrey's way. They told me that they didn't want quality, just a viewable film. The crew felt so bad about the way I was treated that they gave me a party – and usually it's the other way round. I know I've been guilty of excuses but my God what do you have to do to pay your dues? I made Wild Rovers for MGM and kept quiet when they recut it. But this time I couldn't take it. I played fair. They didn't.[11]

Coburn later said "You know, I don’t mind that film. I liked my work on it. There again the studio (MGM) fucked it up. They cut ten days out of the schedule. They pulled the plug on us early. It’s too bad. We did shoot the film on location in Boston though."[13]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The Carey Treatment received mostly mixed to negative reviews from critics.

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 60% based on 5 reviews, with an average score or 5.20/10.[14]

Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times, was amused by The Carey Treatment but wrote, "...I don't think we have to take this too seriously, for The Carey Treatment, like so many respectable private-eye movies, is sustained almost entirely by irrelevancies."[15]

Roger Ebert wrote, "The problem is in the script. There are long, sterile patches of dialog during which nothing at all is communicated. These are no doubt important in order to convey the essential meaninglessness of life, but how can a director make them interesting? Edwards tries."[16]

The Los Angeles Times called it "Edwards' best movie in years" and Coburn's "best role since moving up from supporting player to star."[17]

Variety said it was "written, directed, timed, paced and cast like a feature-for-tv... a serviceable release... Jennifer O'Neill... graces with her beauty plots to which she has absolutely no integral contribution."[18]

Accolades

[edit]- 1973: Nominated, 'Best Motion Picture'

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Peter H. (June 28, 1981). "Julie Andrews: Bye, Mary Poppins, here's a thoroughly modern movie star Julie Andrews changes image from 'Mary Poppins' to 'S.O.B.'". Chicago Tribune. p. k1.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (Feb 15, 2004). "Anatomy of a Blake Edwards Splat". New York Times. p. MT26.

- ^ Martin, Betty (Aug 9, 1968). "'Case of Need' on A&M Slate". Los Angeles Times. p. e12.

- ^ Martin, Betty (Oct 1, 1968). "Irene Pappas Signs Contract". Los Angeles Times. p. c14.

- ^ Judith Martin (28 Feb 1969). "Dropping the Scalpel: Film Notes Columbia Frowns Speeds the Turnover Refuge From Roles". The Washington Post and Times-Herald. p. B12. Turn on hit highlighting for speaking browsers by selecting the Enter buttonHide highlighting.

- ^ A. H. WEILER (July 6, 1969). "No Gap Like the Generation Gap". New York Times. p. D11.

- ^ A. H. WEILER (Mar 21, 1971). "Our 'Boy' Barbra: Our 'Boy' Barbra". New York Times. p. D13.

- ^ Martin, Betty (June 23, 1971). "Comeback for Ida Lupino". Los Angeles Times. p. e7.

- ^ Andrews, Julie (202). Home work : a memoir of my Hollywood years. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 167.

- ^ "MGM Slates Busy Month in September". Los Angeles Times. Aug 27, 1971. p. d11.

- ^ a b Warga, Wayne. (Dec 26, 1971). "What's Going On in the Lion's Den at MGM?: What's Going On". Los Angeles Times. p. q1.

- ^ Servi, Vera. (Dec 20, 1971). "To Viet Nam with Hope". Chicago Tribune. p. b20.

- ^ Goldman, Lowell (Spring 1991). "James Coburn Seven and Seven Is". Psychotronic Video. No. 9. p. 24.

- ^ "The Carey Treatment". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "the-screen--breezy-james-coburn-in---carey-treatment". nytimes.com. 1972-03-30. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ The Carey Treatment Movie Review (1972) | Roger Ebert

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (7 April 1972). "Pathologist as private eye". The Los Angeles Times. p. 15 Part 4.

- ^ "The Carey Treatment". Variety's film reviews. 1983. p. 211.

External links

[edit]- 1972 films

- 1970s crime thriller films

- 1970s mystery thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American detective films

- American mystery thriller films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films about abortion

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on works by Michael Crichton

- Films directed by Blake Edwards

- Films scored by Roy Budd

- Films set in Boston

- Films shot in Boston

- Medical-themed films

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- 1970s American films

- English-language crime thriller films

- English-language mystery thriller films